What is an eruv?

Eruv (עירוב, pronounced aye-roov or eh-roov, plural eruvin) translates literally from the Hebrew as a "mingling" or "mixture." However, in modern speech refers to the joining together or integration of private and public spaces to create one larger domain in which Jews can carry, push strollers, and so on, during the Sabbath and on Jewish holidays without violating any of the 39 melachot, or forbidden activities.

The melacha of hotzah, or carrying/transferring (an object), originates in Exodus 16:29, in which the Israelites are in the desert and God provides the Israelites with manna from Heaven about which the Torah says,

See that the Lord has given you the Sabbath. Therefore, on the sixth day, He gives you bread for two days. Let each man remain in his place; let no man leave his place on the seventh day.

In the Talmud Shabbos 96b, this melacha s further elaborated upon in reference to the account of the man who was executed in Numbers 15:32-36 for collecting wood on the Sabbath. According to the Talmud, the man was executed for violating this very melacha.

Additionally, this melacha is referenced in Jeremiah 17:21-22.

So said the Lord: Beware for your souls and carry no burden on the Sabbath day, nor bring into the gates of Jerusalem. Neither shall you take a burden out of your houses on the Sabbath day nor shall you perform any labor, and you shall hallow the Sabbath day as I commanded your forefathers.

In ancient times most communities and cities were walled, which did not create an issue. However, as times changed and walls were not obligatory and the look of towns and cities changed, the eruv was developed in order to allow an individual to carry an item outside the home, no matter how small or insignificant. For example, a mother carrying a child to a nearby park or a man carrying a prayer book or cane to synagogue would be violating the Sabbath without an eruv.

That being said, an eruv does not give an individual carte blanche to carry whatever he or she wants. For example, an umbrella is an item forbidden on the Sabbath, so it would be forbidden to carry it, even in an eruv. The eruv was established for friends to gather in a park, for a family to go to synagogue together while pushing a stroller or carrying a child, or for an elderly individual to use a wheelchair or cane.

Additionally, this type of eruv is known technically as an eruv chatzeirot (עירוב חצרות), which translates as "mixing ownership of domains." For more on the eruv, as well as the other types of eruv known as eruv tavshilin and the eruv techunim, click here.

How To

Although chapters 1 and 11 of Talmud tractate Shabbat discuss the melacha of carrying or transferring, the essential rules for an eruv were established by Rambam in the Mishnah Torah, Hilchot Eruvin 1:1-7 and 2:10, as well as the Shulchan Aruch Orah Chayim 366:1 and 382:1.

The Talmud explains four types of domain, which are exempt areas, private areas, public areas, and semi-public areas. These designations don't refer to ownership, but rather to layout. Thus, a private area is one that is enclosed by walls that are at least 10 tefachim (about 3 feet) tall, a public area is one that is at least 16 mot (about 28 feet) wide, and so on.

According to this and the Biblical verses of origin, the following rulings (and many more that will not be detailed here but can be found here) were established:

transferring an item from a private to public domain is Biblically forbidden

transferring an item from a semi-public to private or public domain is Rabbinically prohibited

transferring an item from an exempt area to any other domain is permitted

carrying inside one's own private domain is completely permitted

In a perfect world, the borders of any eruv would be solid walls. For example, the Old City of Jerusalem, with its surrounding walls, allows for an individual to leave his or her home and walk in public spaces without violating any prohibitions. But the rabbis dictated that a wall can be a wall without being solid, thanks to the use of doorways.

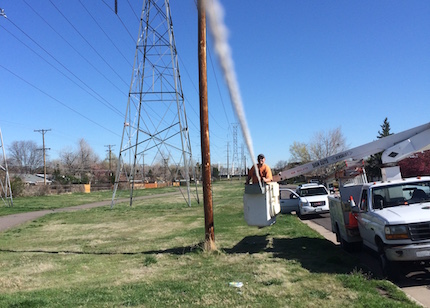

So as a community creates an eruv by establishing physical boundaries, light or power poles are often used as the frames of what would be considered large doorways. Then, a string or wire is hung from one pole to the next to create the lintel in a series of doorways that ultimately make up a wall. In some instances, fences and natural features like a lake or river may be used to delineate an eruv's boundaries, too.

Therefore, the eruv enclosure may be created by telephone poles, for example, which act as the vertical part of a door post in a wall, with the existing cables strung between the poles acting as the lintel of the doorframe. As such, the entire "wall" is actually a series of "doorways." Added to that there may be existing natural boundaries and fences that help establish the eruv.

Constructing an eruv is a complex and very involved job that requires the knowledge of a well-trained rabbi and scholar who knows the most minute of details about measurements, materials, and so much more. We can't detail all of the laws and requirements here, but you can begin to explore them at length visit the Halachipedia or Eruv.org.

Exceptions and Notes

It's important to note that before any Jewish community can begin setting up wires and establishing boundaries that they have to work with local government officials to receive permission and then establish permits and relationships with power companies and other necessary individuals before an ruv can even be set up.

Furthermore, an eruv requires intense maintenance and upkeep. A quick thunderstorm can destroy an eruv in minutes, requiring the community to scramble and get it re-established by Shabbat, lest it keep young children, the elderly, or the infirm indoors. In fact, most communities have an active "eruv status" website or messaging system to let community members know the ruv's status.

Also, there are many Jews and Jewish communities who do not view the eruv as an option to circumvent the melacha of carrying. Among these are Chabad Lubavitch Jews, the community of the Lower East Side of New York City, and others. Some of these communities are concerned that the use of an eruv creates a stumbling block because if the eruv is down, and someone doesn't know, they'll perform a melacha and violate the Sabbath, while others are concerned that it will create carelessness where individuals will take for granted that carrying is forbidden on the Sabbath.

In these communities, many women with small children are unable to make it to synagogue, and men will wear their tallit (prayer shawl) to synagogue as opposed to carrying it. Likewise, these communities have developed creative ways of making sure they have their house key on them over the years. It became a fashion at one time for men to turn their house keys into tie clips or into a key belt, or for women to have their house key turned into a broach or other piece of jewelry that can be worn rather than carried.

Unfortunately, although carrying a child in a carrier has become commonly known as "baby wearing," as it is not an article of clothing or an accessory, wearing a child in a carrier would be forbidden without an eruv. Read more about carrying a child on Shabbat and possible solutions here.